I created this blog, Mr. Coates' History Class, as a tool for a hypothetical eleventh grade US History II class, and, over the month that I worked on it, I curated articles as if the classroom's units were spanning the years 1948 to 1963, focusing mainly on US history but including international events when appropriate. I personally wrote five longer form blogs, and included three written by friends who were writing as if they were my students. I also posted four shorter entries, with links to videos and podcasts, often ending with prompts that my pretend students would write. My blog also included a poll, a contact form, links to more resources, a section for upcoming homework assignment reminders, and an easily navigable directory of past articles. In addition to these sections of the blog itself, I also created a teacher twitter, @coateshistory , which I used as if I were teaching a course that used this blog and I posted on it whenever I had updated the blog.

This was easily my favorite assignment for this class (and perhaps any of my classes) this semester. I really enjoyed getting to design a blog, getting to write articles to a student audience, and enlisting my friends to write articles and to comment on mine (check out the comments on some of these entries to see what I am talking about, specifically the Eisenhower farewell address entry). I had had some previous experience using Blogger, as I used to run a film blog using it, so it was great to try new things within a comfortable framework. I would definitely try to do something similar to this if I found a class I thought I could integrate it well with, and I look forward to this prospect. The only problem with Blogger, and it was not a very big one at that, was that I could not play with the layout or format as much as I would have liked. I am happy with what I ended up with, but at times I was frustrated as I tried to change the way things were laid out and I found myself not being able to do it.

My advice to future students taking this course is to have fun with this project - if it starts feeling like a lot of work, try something else. Only write a blog if the prospect really excites you - while this was a joy to create it also was a lot of work, as I had to do research for each entry and ask several friends to get involved, and I had to be able to work around their schedules. I also had to work on it pretty consistently over two months to get an authentic blog feel - it would not have done to have posted all the articles at once. Experiment with different tools - the internet has several options for whatever you are trying to do. Be careful in writing your rubrics - that was the hardest part of this, in my opinion, as I was having trouble conceptualizing what my project would end up looking like. Be clear in the language you are using and do not trap yourself into doing things you might not be able to do.

Thank you to everyone who read, in my course and outside of it. I look forward to returning to history blogging someday soon.

A blog for Mr. Coates' US History II classes for the 2016-2017 academic year.

Sunday, December 4, 2016

Thursday, December 1, 2016

Who killed JFK Podcast

As we start to reach the time period before the holidays, we are going to continue delving into the presidency and assassination of John F. Kennedy. We are to have a special guest speaker deliver a presentation on this subject by the end of next week, so make sure to familiarize yourself with this historical event. To that end, I invite you to listen to this podcast from Stuff You Should Know titled "Who Killed JFK?" by following this link: http://www.stuffyoushouldknow.com/podcasts/killed-jfk.htm

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

Fidel Castro: Revolutionary and/or Tyrant

1926 - 2016

With the death of Fidel Castro Friday night and our shift in

focus from the Eisenhower administration to that of John F. Kennedy, it seems

appropriate that we look at the rise to power of Castro and why he, almost

sixty years later, still has politicians worldwide fiercely debating his place

in history.

On New

Years Day 1959, Cuban Dictator Fulgencio Batista was forced to flee the country

from Havana airport, following Castro’s successful guerilla war in the island

nation. Batista had ruled the country since 1952, and had actually imprisoned

Castro in 1953, but released him in an effort to appear less like a dictator. The

released Castro travelled to Cuba with a handful of allies, included his

brother Raul Castro and the revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara. What happened

next is nothing short of incredible – travelling through rough seas for over

1,200 miles on a decrepit yacht called the Granma,

Castro and eighty fellow revolutionaries invaded Cuba on 2 December 1956. Hiding

in the mountains, Castro began to lead a guerilla campaign against the Batista

government, and this campaign was able to connect with the Cuban people.

Castro’s transition

to power in 1959 was anything but smooth. Early supporters who had hoped he

would end the dictatorship of Batista and bring democracy to Cuba, were

dismayed as he began to align himself to the Soviet Union, going so far as to

describe himself as a Marxist-Leninist in a speech around this time. In

response to demands that the US withdraw all but eighteen members from their

embassy in Havana, Eisenhower ordered that the US embassy close; it wouldn’t

reopen until 2015. An embargo from the US soon followed, forcing Cuba to rely

heavily on the Soviet Union to buy their sugar and otherwise prop it up economically.

The embargo

would prove to be the least of Cuba’s worries from the United States. On April

17, 1961, three months into the presidency of John F. Kennedy, a

counterrevolutionary army of over 1,400 exiled Cubans, armed and funded by the

CIA, attempted an invasion of Cuba, by way of creating a beach head at the Bay

of Pigs. Castro was prepared for this, and slaughtered the soldiers as they

landed. The counterrevolutionaries were not given the required air nor naval

power, and had failed to take the Cubans by surprised. The invasion was a

spectacular failure, and a complete surrender was offered after only three

days.

From the

Bay of Pigs invasion onwards, Castro would have firm evidence to show that the

United States could not be trusted. The ninety miles between Florida and Cuba

became a sea of distrust and suspicion. Increasingly paranoid, Castro requested

ballistic missiles from Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Union, to

deter future aggression from the United States. President Kennedy was not about

to let missiles to be held so close to the US border, so he sent naval ships

down to blockade the incoming Soviet ships. For thirteen days the heads of both

the United States and the Soviet Union scrambled for a diplomatic solution – in

the end, the Soviets turned around and went home, and the United States agreed

to pull its Jupiter missiles out of Turkey.

This successful

aversion of conflict by the Kennedy administration kept the Cubans from

becoming an existential threat. Castro stayed on as dictator for the next

forty-four years, but we have now reached the end of the history of what we are

concerned with in our class. Fidel Castro, the leader of a Caribbean nation of

eleven million people, certainly punched above his weight. No leader besides

Queen Elizabeth II held onto power longer in the western world. He jailed and executed

rivals, he suppressed free speech, and he continually agitated the United

States. He also improved the country’s access to quality healthcare, brought

about racial integration, and was to a degree successful in managing an economy

without any aid or trade from the United States. His legacy will remain hotly

debated by historians for years to come

Monday, November 28, 2016

John F. Kennedy Inaugural Address

Sunday, November 20, 2016

Three Songs

Listen to these songs by Phil Ochs and Bob Dylan. Read the lyrics along with them. How do these songs reinforce the culture of the 1960s? What are they referring to, specifically - such as when Ochs says "I hate Joe Enlai, I hope he dies"? Draw examples directly from the lyrics. Find one other song from the 1960s that fits these themes. Two paragraphs, due Wednesday.

Monday, November 7, 2016

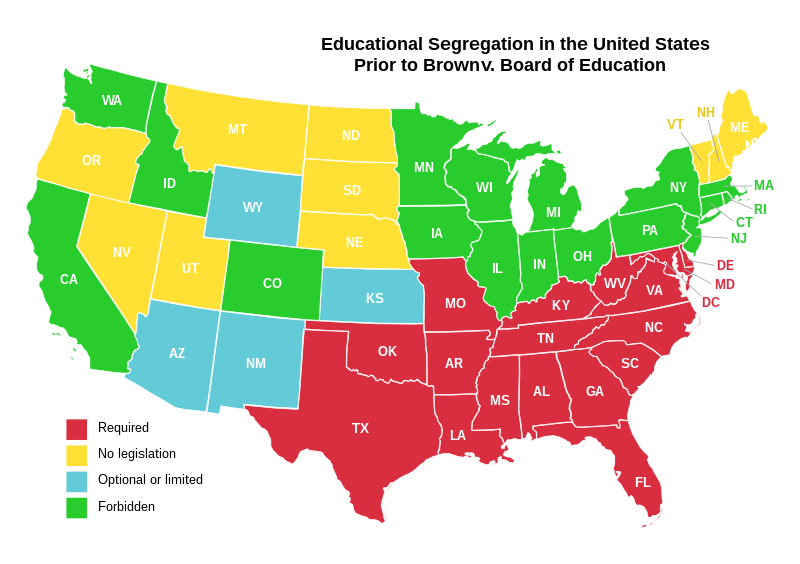

Student Blog: Constitutionality and Brown v. Board

In 1954, the

United States Supreme Court declared that “separate, but equal” was no longer

constitutional in the United States, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson, and idealistically forcing an equal society for

the first time in U.S. history. The problem? That’s not quite what the decision

said.

Let’s

begin with the background—what lawyers refer to as “the facts of the case.” Thirteen

parents of Topeka, Kansas, public school students filed a class action to force

the district to reverse its policy of racial segregation. The plaintiffs lost

in the district court because, even though the court found that segregation in

public education had a detrimental effect on African-American children, the

schools were substantially equal with respect to buildings, transportation,

curricula, and education. By the time the case went to the Supreme Court, it

had been consolidated with five other cases representative of five other

states, all of which were sponsored by the NAACP. Fun fact: the lead attorney

on this case was Thurgood Marshall.

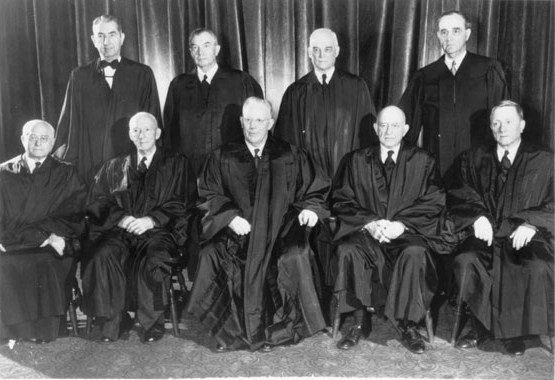

Things

went differently in the Supreme Court. First, the Court didn’t decide the case

in its first hearing. It asked for a second argument a year after to focus

specifically on the issues raised by the Equal Protection Clause. Second,

before that subsequent hearing, one of the very conservative justices died—to be replaced by Earl Warren, the architect of the single most liberal

Supreme Court in this nation’s history. Thus, in a sixteen page per curiam decision (per curiam being fancy Latin for a

unanimous court), the Court struck down racial segregation. The holding was

quite literally that segregated black and white schools of equal quality were

still harmful to black students, and therefore had to be unconstitutional under

the Equal Protection Clause.

The Warren Court

But

that is where this gets really

interesting. Two points: first, the Supreme Court relied on social science for

the first time in making this decision. The Court pointed to psychology and

other social science studies about the effect of segregation of the

African-American psyche. This was an unprecedented step. To that date, the

Supreme Court had based its decision in legal precedent and statutory

interpretation. To go beyond that, one might argue, was more akin to creating legislation,

rather than judging the law. And as we all know, the power to legislate rests

only with Congress. Second, and most importantly, the Supreme Court did not

automatically end segregation. Contrary to popular belief, Brown told the states to change “with all deliberate speed.” What

does all deliberate speed mean?” No one

really knows.

In

the end, it took a second decision for the Court to delegate orders that

desegregation occur. And it’s taken repeated litigation efforts to get the

Court to not only reaffirm its commitment to what has become affirmative

action, but also to make communities respect the mandate. The Supreme Court has

had to repeatedly decide cases about how schools should be run; how they should

treat their students; how busing routes should be driven; and

more. This may seem like what the Supreme Court is supposed to do, but let’s

remember the contours of the actual decision: was Brown meant to go that far? Or should Congress have stepped in and

done the actual governing? Should the individual state communities have created

their school standards? Should the Court have reviewed them on appeal, rather

than created the guidelines that individual communities then had to wrestle

with?

All these answers depend on your view of the Court’s role in our constitutional

structure. But at the end of the day, only the right to equality exists in the

Constitution. Separate but equal is unconstitutional. And so, perhaps, is a

Court that legislates from the bench.

By Laura Ferguson

Sunday, November 6, 2016

The Korean War: Police Action

The Korean Demilitarized Zone

Roughly

halfway down the Korean peninsula lies the Demilitarized Zone, an armored

border stretching roughly two hundred and fifty miles from the east coast to

the west coast and about two and a half miles wide throughout. This border

divides the peninsula into The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or North Korea,

from the Republic of Korea, or South Korea. This border, which runs on the 38th

latitudinal parallel, holds in place a shaky cease-fire that was signed in 1953

following the end of the Korean War. How and why was Korea divided? To

understand that we must turn the clocks back to the late 1940s, and trace the

origins and the fallout of the Korean War.

Towards the end of the Second World War the Soviet Union joined her allies in the war against

Japan. Soviet troops made their way halfway down the Korean peninsula before

the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki signalled the end of the war, and

thereafter Korea was occupied and controlled by a joint Soviet and American

Military Government. This commission failed to make progress on creating an

independent Korea, and elections held in 1948 attempting to set up a new

sovereign state were met with boycotts and violence from the Korean communists.

The results of these elections set up a government located in the Southern city

of Seoul, while the Soviets set up a communist government based out of

Pyongyang soon thereafter, led by a man named Kim Il-Sung. This was followed by the United States

and Soviet Union pulling out of the Korean peninsula by 1949, and allowing

these two new states to develop on their own. Both sides, however, began planning for future reunification - peacefully or otherwise.

In

1950 Kim Il-Sung, backed politically and economically by the Soviet Union and

militarily by the newly formed Communist Chinese state, invaded South Korea,

believing that the people would welcome him as a liberator. As Russia was

boycotting United Nations meetings and the Communist Chinese weren’t yet internationally recognized, the Security Council voted unanimously to have member states

support South Korea militarily that June. However, by September the

Communists had overrun almost the entirety of South Korea; something drastic

was needed. On September 15, the United Nations began the battle of Inchon, an amphibious invasion under the

command of General Douglas MacArthur that provided a clear victory and a

strategic reversal. Within the next two months

MacArthur’s forces would push their way northwards, soon making their way

passed the 38th parallel and eventually to within miles of the

Chinese border. This was met with a major invasion by the Chinese, which pushed

the fighting back to the 38th parallel, where the fighting was localized

for the remainder of the war.

These

quick troop movements up and down the peninsula before settling into a longer

stalemate at the 38th parallel were incredibly deadly. The majority of the

war’s casualties fell in this period, which included some 2.5 million between both

sides. Halfway through 1951 both countries accepted that they had reached a

stalemate, and little territory was exchanged as fighting continued. General

MacArthur argued that the allies should extend the war into China, which was rebuked by the US government as many feared this would lead to another world war. He sent cables to members of the House of Representatives

defending his position, and in response President Harry Truman demanded his

resignation. Over the next two years, the two Koreas sought to create a peace

deal, but no resolution could be found that both sides could find agreeable.

During these two years of protracted negotiation Dwight Eisenhower was elected

US President. He had campaigned on ending the Korean War, and immediately set

out to do so. In 1953 an agreement was reached, not in the form of a treaty, but rather a cease-fire;

to this day, the two Koreas technically remain at war.

Discussion

questions, write a paragraph for one:

In many Anglophonic nations, the Korean War

is referred to as the “Forgotten War” – why might this be the case?

Was the United Nations right to act on a

vote that would put the members at war with the Soviet Union and China when

neither was represented in the vote? Why or why not?

President Truman famously referred to the war as "Police Action" - why might he choose to use this phrase to describe such a brutal war that had broad international support?

Saturday, October 29, 2016

Student Blog: Japan's Turn to Pacifism

For

most of today’s young Americans, modern Japan brings to mind anime, sushi, and

all things strange. Probe people for something about Japan with a bit more

historical significance and two locations will immediately come forward: Pearl

Harbor and Hiroshima. Studies of US-Japan relations for most Americans begin

with the former and end with the latter. Studies of US-Japan relations for most

Japanese begin with the latter. It thus surprises many Americans when they

learn that Japan is constitutionally prohibited from going to war.

Imperial

Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, accepting the terms laid out in

accordance with the Potsdam Declaration. To reach this point, Japan had not

only endured the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but also the

wholesale firebombing of most of its major cities, which killed hundreds of

thousands of civilians. Even then, the higher ups in the military wanted to

continue the fight. It was only the intervention of Emperor Hirohito himself

that finally compelled the military to surrender…Why did they go so far?

The

Potsdam Declaration called for, in addition to relinquishing conquered

territories, Japan’s “unconditional surrender.” To the higher ups, this meant

the dismantling of the Japanese imperial nation-state as it had existed since

1868, and further, the potential dissolution of the imperial system in its

entirety. For the last 1,000 of the roughly 2,600 years (a good portion likely

mythical) of the imperial line, the emperor had not been much more than a

symbol, often to legitimize the rule of powerful samurai families. The Meiji

Restoration of 1868 put an end to feudal Japan and samurai rule, creating a

modern, constitutional state with the emperor at its center. Vestiges of

samurai culture would persist, but lay dormant as Japan modernized over half a

century, only coming back to the fore as the military took control of the

country in the 1930s.

MacArthur with Hirohito

Though

the allied forces did end up abolishing the “Empire of Japan” during the

occupation from 1945 to 1952, in a turn of events that surprised even Emperor

Hirohito himself, the U.S. decided not

to force his abdication and abolish the imperial system. This was not, of

course, out of some respect for the ancient tradition, but for—much like the

samurai of old—utilizing the imperial institution to more easily maintain

control over and carry out reforms of occupied Japan.

Indeed,

Emperor Hirohito had one of the most unique experiences in human history: from

being worshiped as a living god and the bedrock of the militarist state that

compelled its citizens to fight and die in his name, to being “the symbol of

the State and of the unity of the People, deriving his position from the will

of the people with whom resides sovereign power” (Constitution of Japan).

Moreover, this new Japanese “State” would make pacifism one of its most

important values, expressed through Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution

established in 1947, which fundamentally renounces war as a political tool of

the state.

Article 9. Aspiring sincerely to

an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever

renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force

as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of

the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war

potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state

will not be recognized.

However,

with the victory of the Communist Party of China in the Chinese Civil War in

1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, the U.S. backtracked its

position on the matter and Japan would create a “Self Defense Force” in the

1950s consisting of land, sea, and air forces with a legal status that views it

as an extension of the national police force prohibited from engaging in

conflict unless Japan is directly attacked. Extensions of the size and role of

the Self Defense Force remains a contentious issue within Japan and the call to

revise Article 9 by the current ruling party are as of now widely unpopular

among Japanese. Time will tell if the push of certain domestic politicians

coupled with changing geopolitical conditions, a rising China and a potential

retreat of the US military from the Asia-Pacific region will lead Japan to once

again have an unrestricted military.

By Matt D'Elia

By Matt D'Elia

The Nifty Fifties

Baby Boomers, Dwight Eisenhower, full employment,

poodle skirts and Leave it To Beaver. These are some of the hallmarks of the

1950s, a decade which saw the rapid growth of the US economy that has since

left it as, how many a politician will articulate it, "the greatest

country on Earth". Following the Second World War, the United States was

the only nation which had emerged with its economy, borders, and population

intact. The decades of depression and war, which had seen the unemployment rate

jump to a high of 24%, were over. A growing middle class was moving from

the cities into the suburbs, having lots of children, and achieving their

aspirational dreams of home ownership.

This was the decade of American

prosperity, and this was reflected in the culture. TV shows such as Leave it To Beaver helped to emphasize “education, occupation,

marriage and family … as requisites for a happy and productive life.” A young

truck driver from Tennessee named Elvis Presley was discovered recording a song

for his mother at a studio and became on overnight sensation. A movie star

named Marilyn Monroe became one of America’s first, and easily most

recognizable, sex symbol. Authors such as Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs

experimented with literature to create new forms, now known as beat poetry.

In terms of foreign affairs,

America had pivoted from worries about her former enemies in Japan and Germany

to the Soviet Union. Inside of the United States, a senator from Wisconsin

named Joe McCarthy fueled tensions by claiming that members of the State Department,

the Truman administration, and the film industry were communists, causing what

became known as the “Red Scare”. Many people unfairly lost their jobs after

having to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. McCarthy

was ultimately censured by the Senate in 1954 and died of alcoholism in 1957,

but his name has since been synonymous with witch hunting in American politics.

The Russians, for their part, scared the American populace more than McCarthy

ever could by launching Sputnik, the first satellite that made it into space,

in 1957.

The 1950s were also the decade

that America had to come to stark terms with the problems of segregation and

racial violence. A young Baptist preacher named Martin Luther King began to

organize bus boycotts and marches in 1955. Later that year, a young

secretary named Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus, leading to a

publicized arrest which drew American attention to civil rights issues. Most

important was the unanimous Supreme Court decision for Brown Vs Board of

Education of Topeka Kansas of the year before that stated that Separate but

Equal was unconstitutional, and that schools would have to integrate. President

Eisenhower was forced to call in the National Guard to Arkansas when the governor

refused to end segregation in this state.

The 1950s were a turning point

for America; as British power was waning, the title of World Super Power was

transferred to the United States, with only the Soviet Union able to contest

this. Inside the borders, Americans were working more, having more children,

and building long term wealth. The issues of civil rights, long ignored, were

finally coming to the forefront. This changing of the guard was reflected in

the music, film, and literature of the time, giving rise to the dominance of

American culture more globally.

Assignment: Watch this episode of Leave it To Beaver, and write two paragraphs describing what 1950s values the episode is reflecting. Due in class Monday.

Monday, October 24, 2016

Student Blog: Blood, Money, and Oil: Iran in 1953

The year of 1953 proved one of the

more fateful in the history of American foreign policy. The headline grabbing

concerns of the age – nuclear war, communist expansion – certainly overshadowed

the goings on of a then little thought of nation in the Middle East – Iran.

Listening to the mass media and

political posturing coming from the United States today may leave you with the

view that Iran is perhaps one of the most virulent enemies of the West. The use

of synecdoche here and ubiquitously throughout the short hand of geopolitics is

dangerous to say the least. One must take into account most Iranians are not

fond of their government – much in the same way that most Americans are not

fond of their government. And that the use of the name of a nation to describe

the actions of its government paints the entire population of that nation with

the same brush. Thus when a US President calls Iran evil, he

ends up calling

millions of innocent and potentially sympathetic Iranian citizens evil. The

racism here should be obvious. But as an experiment, this article will use this

same manner of discourse to refer to the actions of a handful of actors within

the US government in the discussion of a successful coup in Iran that took

place in 1953.

The roots of the coup are complex

but America’s involvement (and by America I mean any and all US citizens living

or dead) is really quite simple. The twentieth century will be remembered in

Middle East as the century in which everything about everything changed

irreversibly. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the discovery of oil would

welcome years of Western meddling, leading towards generation after generation

of armed conflict. For Iran, this destructive course was initiated by the

efforts of a man named William Knox D’Arcy who in 1908 successfully negotiated

a concession with Qajar dynasty for near total control of oil output from

Persia. Thus the Anglo-Persian Oil company was formed, later the Anglo-Iranian

Oil company, later British Petroleum aka BP (Yeah, these guys are batting a

thousand). This cushy position would continue through the First and Second World

Wars, several regime changes, and right to the birth of the modern state of

Iran.

Mohammed Mosaddegh

This is where things get tricky for

our good friends at the AIOC (Anglo-Iranian Oil Company). In the early 1950’s a

man by name of Mohammad Mosaddegh was voted into the office of Prime Minister

of Iran, and he, being a man of the modern era, a republican, not exactly tied

to any sense of loyalty to past monarchies and their deals with shady no longer

living British aristocratic oil speculators, begins agitating for

nationalization of the oil industry. Now naturally this kind of commie nonsense

was not going to be tolerated by the powers that be, that being the powers that

be in the White House. With some shrewd maneuvering, the AIOC was able to get

the ear of the Dulles Brothers, ardent cold warriors with an inside track to

the President – at the time – Dwight Eisenhower. What happens next is sort of

amazing. A man named Kermit Roosevelt acting on behalf of the CIA flies into

Tehran with a suitcase full of cash. He begins paying off anyone that will

listen to him, building up a coalition to overthrow the prime minister’s

government and replace it with a US backed dictatorship.

I think I just sank the Search Engine

Optimization of this blog post. Mosaddegh was replaced with a western puppet

known as the Shah who was in turn overthrown in 1979. When the dust settled a

harshly anti-western government stood in his place. So if you never understood,

America, why Iran hates you so much… that’s why.

By John Kluxen

Eisenhower's Farewell Address

On January 17 1961, a few days before leaving office, President Dwight Eisenhower delivered his farewell address, where he raised the issue of the Military Industrial Complex. Please watch the video and answer the following questions in the comments.

1) How did the Presidency of Eisenhower influence his views on the military?

2) What does Eisenhower mean when he refers to the Military Industrial Complex? What is he saying about it?

3) How can we view the speech differently today than it was viewed in Eisenhower's own time?

Friday, October 21, 2016

Origins of the Vietnam War

On

September 2, 1945, shortly following the surrender of the Empire of Japan in

World War II, Ho Chi Minh issued the Proclamation of Independence for the

Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Ho was a leader in the Viet Minh independence

movement since the war and had previously lived in the US, the UK, France, the

Soviet Union and China. His proclamation begins by directly quoting from the US

Declaration of Independence and France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and

Citizen:

All men are created equal;

they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights; among these

are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

This immortal statement was made in the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America in

1776. In a broader sense, this means: All the peoples on the earth are equal

from birth, all the peoples have a right to live, to be happy and free.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of the French Revolution made in 1791

also states: All men are born

free and with equal rights, and must always remain free and have equal rights.

Despite

this shared rhetoric, the French had only just regained control of their

Indochinese colony from the Japanese, and were not about to let Vietnam become

an independent state. What’s worse was that Ho Chi Minh was not trying to

establish a new capitalist republic, but rather a communist state, something

that western countries found unacceptable. The French authority immediately

took up the task of taking down this insurgency, backed with weapons from the

United States. Ho’s forces began to mobilize stronger and receive supplies from

the Soviet Union, and by the end of the forties a full scale war had broken

out. The French sent troops from all over their massive empire to try to quell

the rebellion, but after a decisive loss in 1954 at Dien Bien Phu they decided

to cut their losses and agree to meet to discuss peace terms.

The terms

were settled in Geneva, Switzerland, and stated that Vietnam would be split in

two; the Communists would gain control of the North, while the South would be a

republic that would be given the chance to decide a separate future. An

election was rigged up by the United States and the family of a man named Ngo

Dinh Diem. Diem became the first president of the Republic of Vietnam, and

future elections were canceled. The Eisenhower administration’s internal

polling suggested that the communists could have won about percent of the vote

in this election, and their main concern was keeping the communists out of

power – not creating a democracy.

Diem’s rise to power brought about resentment from the communists in the south,

who began to launch guerilla attacks under the name of the National Liberation

Front (NLF, or Viet Cong) on Republican targets. In response, Diem executed

anyone he could who was guilty of committing political violence, but it was

clear that he did not have the resources needed to fight the Viet Cong on his

own.

President Eisenhower shakes President Diem's Hand in 1954.

In response

to the growing restlessness in the Republic of Vietnam the United States under

President John F Kennedy began to send over military experts to advise the Army

of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). Whereas Eisenhower had sent only nine

hundred such advisors, Kennedy sent sixteen thousand. This was accompanied by

increased military activity in the Southern Vietnamese countryside, and ARVN

often came up short against the Viet Cong in battle. The Vietnamese military

high command was growing increasingly impatient with what they perceived as the

weakness for Ngo Dinh Diem, as was the administration of the United States.

Diem became increasingly difficult to work with, and he called for campaigns

that the US did not want to support. In early November of 1963, the CIA

authorized ARVN Generals to overthrow and execute Diem. President Kennedy would

fall to an assassin’s bullet himself less than three weeks later.

Wednesday, October 19, 2016

The US Presidential Election of 1948

The

election of 1948 is often considered a landmark election in the history of the

United States. Under Franklin Roosevelt, the Democrats had won landslide

elections in 1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944. But tragedy struck the United States

when Roosevelt died in April of 1945. The war in Europe was weeks away from

concluding, and Adolf Hitler himself would commit suicide before the month was

out, but the war with Japan raged on. Roosevelt’s death caused his Vice

President, a former Senator from Missouri named Harry Truman, to step into the

Oval Office and become the 33rd President.

Truman

represents a few unique points in American history. He is the only man to have

been the third Vice President to a single President. He is the only President

who fought in the First World War. He was the last President to have not gone

to college. Cool and moderate, Truman had been chosen as a compromise when

Roosevelt ran for re-election in 1944. Those closest to Roosevelt knew of his

ill health, and two camps emerged in the Democratic party over whether or not to keep on the pro labor

and pro civil rights Vice President Henry Wallace, or to replace him with Senator James

Byrnes, a more conservative southerner. Truman was chosen to placate both the

Wallace supporters and Byrnes supporters, and was placed on the ballot with

much enthusiasm. Together, Truman and Roosevelt would go on to win thirty six

states in the 1944 election, handily defeating Governor Thomas Dewey of New

York.

Once

elected, however, Truman was never very close to Roosevelt, and seemed to lack

any individual popularity. In fact Roosevelt never told Truman about the atomic

bombs that Truman would late authorize to be used against Japan. Truman may

have been president during the wars end, but he was never able to claim any

credit for it. He was able to help institute the Marshall Plan, but another

man's name was attached to the project so again, Truman wasn’t able to claim

credit. When he introduced a health care bill to Congress after the war's end, it

was shot down as well. Truman was seen as an accidental President, only there

because of Roosevelt’s death. Things only got worse in 1946 when the

Republicans gained majorities in both the Senate and House of Representatives.

This Congress refused to work with Truman, and went so far as to start repealing

legislation from Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Truman used his Presidential

Veto to prevent any wholesale repealing, but it seemed like he was done.

So in 1948

the Republicans believed that they would easily win the presidential election.

Thomas Dewey, who had run against Roosevelt in 1944, was again their nominee.

The Democrats failed to rally around Truman and split into three parties.

Strom Thurmond, a southern segregationist, feared that the Democrats might

force integration, so he formed a political party called the Dixiecrats. Former

Vice President Henry Wallace, fearing that the democrats wouldn’t do enough for civil rights, formed a

political party called the Progressive Party. The conventional wisdom was that

these parties would siphon off votes from the Democrats, and the polling seemed

to confirm this.

Election

day in 1948 fell on November 2. Truman had run a low money campaign, whereas

Dewey’s campaign had raised substantial sums. Truman’s inner circle had already

begun accepting other jobs, resigned to the fact that their man would lose.

Truman slept through the night, whereas Dewey stayed up to watch the returns.

The Chicago Daily Tribune was so sure

that Dewey would win that they went ahead and printed their newspapers with the

headline "Dewey Defeats Truman". As the

results came in, Truman took the lead in votes, a lead that he would never

lose. Surprise! Harry Truman won by a comfortable three point margin – his

detractors had underestimated him, and he would remain President for another four

years.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)