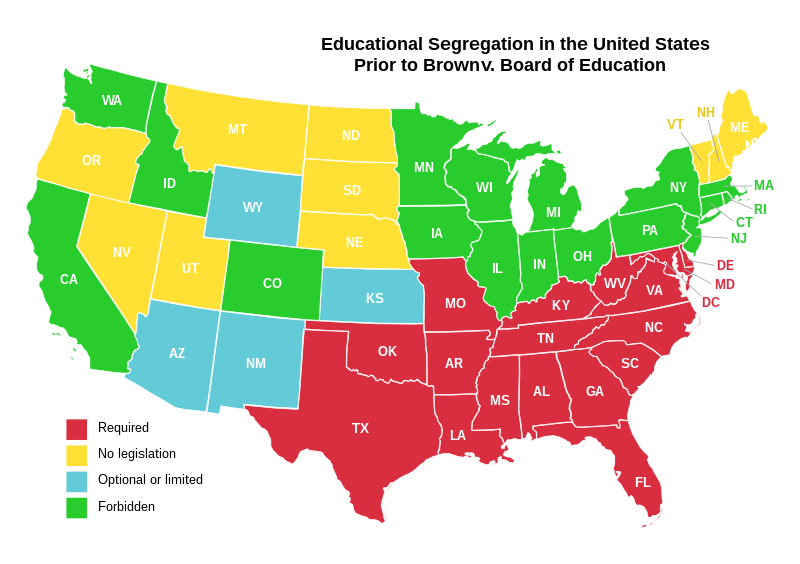

In 1954, the

United States Supreme Court declared that “separate, but equal” was no longer

constitutional in the United States, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson, and idealistically forcing an equal society for

the first time in U.S. history. The problem? That’s not quite what the decision

said.

Let’s

begin with the background—what lawyers refer to as “the facts of the case.” Thirteen

parents of Topeka, Kansas, public school students filed a class action to force

the district to reverse its policy of racial segregation. The plaintiffs lost

in the district court because, even though the court found that segregation in

public education had a detrimental effect on African-American children, the

schools were substantially equal with respect to buildings, transportation,

curricula, and education. By the time the case went to the Supreme Court, it

had been consolidated with five other cases representative of five other

states, all of which were sponsored by the NAACP. Fun fact: the lead attorney

on this case was Thurgood Marshall.

Things

went differently in the Supreme Court. First, the Court didn’t decide the case

in its first hearing. It asked for a second argument a year after to focus

specifically on the issues raised by the Equal Protection Clause. Second,

before that subsequent hearing, one of the very conservative justices died—to be replaced by Earl Warren, the architect of the single most liberal

Supreme Court in this nation’s history. Thus, in a sixteen page per curiam decision (per curiam being fancy Latin for a

unanimous court), the Court struck down racial segregation. The holding was

quite literally that segregated black and white schools of equal quality were

still harmful to black students, and therefore had to be unconstitutional under

the Equal Protection Clause.

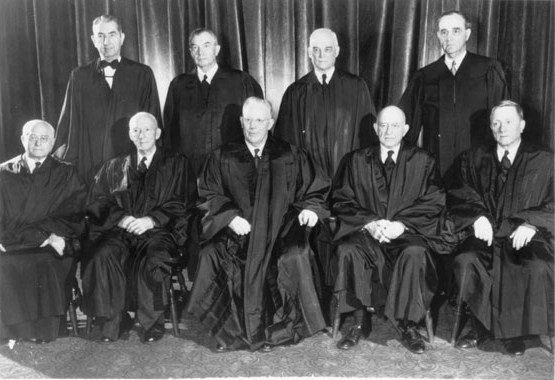

The Warren Court

But

that is where this gets really

interesting. Two points: first, the Supreme Court relied on social science for

the first time in making this decision. The Court pointed to psychology and

other social science studies about the effect of segregation of the

African-American psyche. This was an unprecedented step. To that date, the

Supreme Court had based its decision in legal precedent and statutory

interpretation. To go beyond that, one might argue, was more akin to creating legislation,

rather than judging the law. And as we all know, the power to legislate rests

only with Congress. Second, and most importantly, the Supreme Court did not

automatically end segregation. Contrary to popular belief, Brown told the states to change “with all deliberate speed.” What

does all deliberate speed mean?” No one

really knows.

In

the end, it took a second decision for the Court to delegate orders that

desegregation occur. And it’s taken repeated litigation efforts to get the

Court to not only reaffirm its commitment to what has become affirmative

action, but also to make communities respect the mandate. The Supreme Court has

had to repeatedly decide cases about how schools should be run; how they should

treat their students; how busing routes should be driven; and

more. This may seem like what the Supreme Court is supposed to do, but let’s

remember the contours of the actual decision: was Brown meant to go that far? Or should Congress have stepped in and

done the actual governing? Should the individual state communities have created

their school standards? Should the Court have reviewed them on appeal, rather

than created the guidelines that individual communities then had to wrestle

with?

All these answers depend on your view of the Court’s role in our constitutional

structure. But at the end of the day, only the right to equality exists in the

Constitution. Separate but equal is unconstitutional. And so, perhaps, is a

Court that legislates from the bench.

By Laura Ferguson

No comments:

Post a Comment